Vhils in Providência

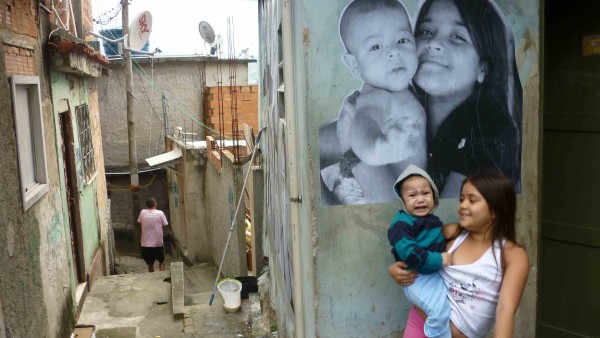

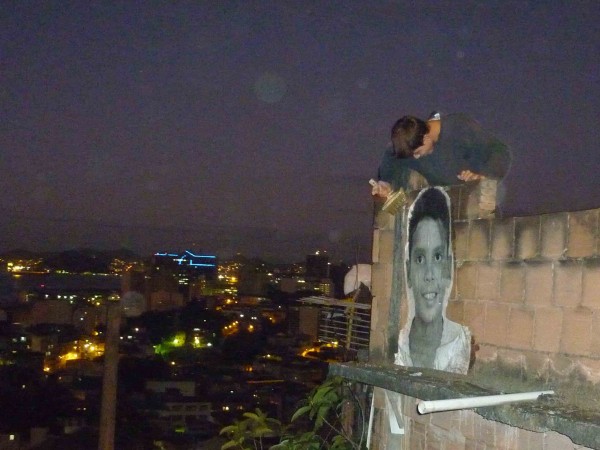

“When I work I build a relationship with space and people. I’ve been working here in Providência for 3 weeks.”

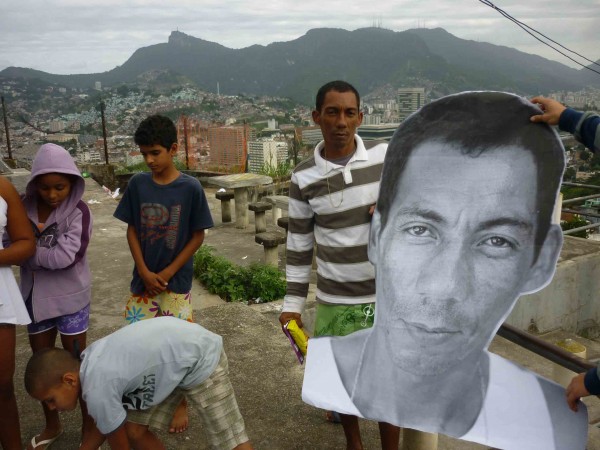

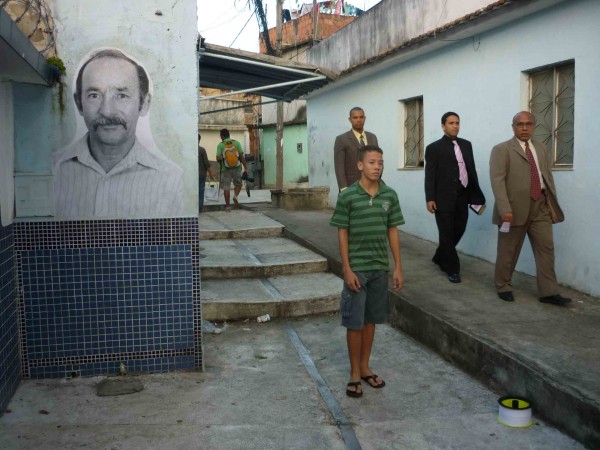

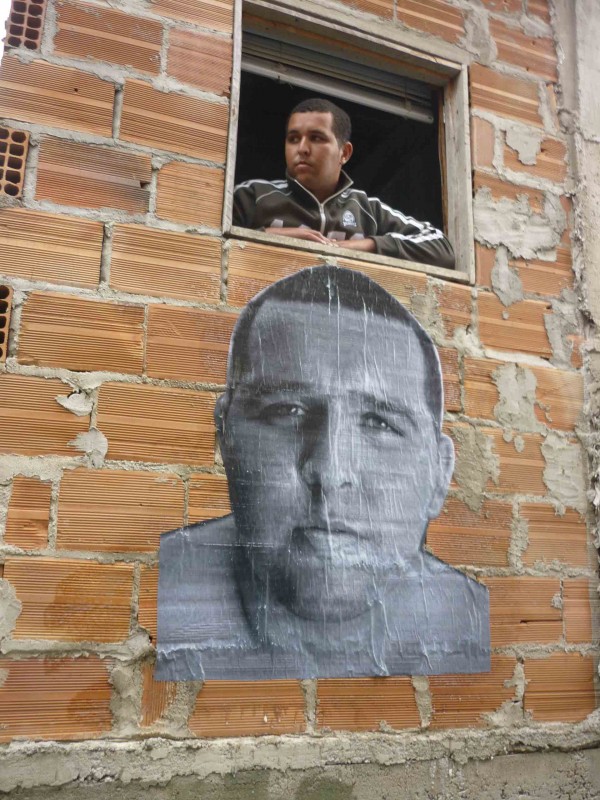

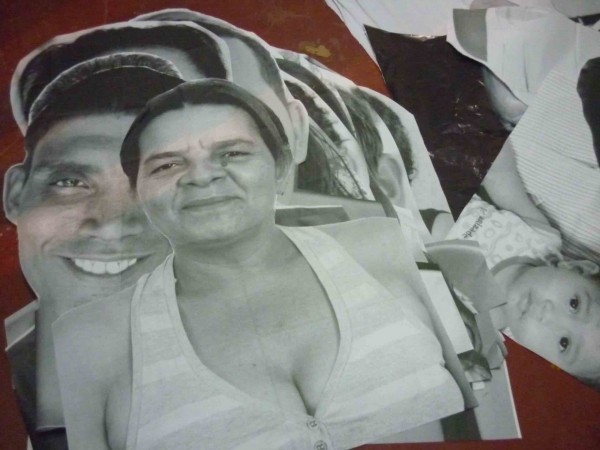

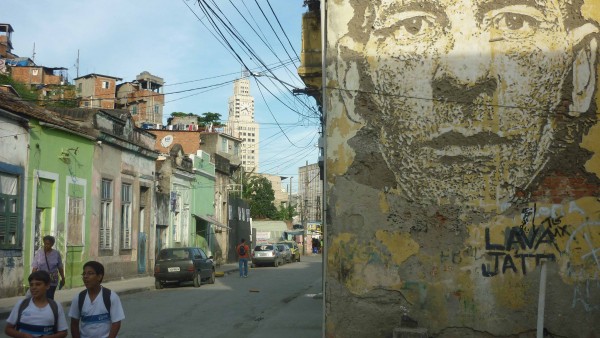

In October 2012 I meet Portuguese artist Vhils in Providênca. The first favela in the world is now the centre of Rio’s “Big Leap Forward”. I haven’t been here for months, and I can’t believe my eyes. The praça, always centre of social life in the favela, is now a dystopian twenty four hour building site. An enormous pillar, a support for Rio’s latest cable car project, has replaced what used to be the sports court. This was where everyone met, where parties took place and where children played. It’s development at breakneck speed, and as usual, favela residents appear to have been granted antlike status in the process. It is a timely moment for Vhils to chisel his moving portraits of residents into the rapidly disappearing walls.

Vhils says:

“Between 1920 and 1974 Portugal lived the Salazar dictatorship. At the end of this the country swung to the left. Growing up, the first art I saw in the street was fading, decrepit murals painted by supporters of the socialists. In the years after Portugal joined the European union in 1986 there was a capitalist boom. Now two competing visual languages covered public walls. Billboards encouraging consumerism surrounded the political murals. Much of the advertising was illegal. Then graffiti began to appear in the mid 1990s. There were more adverts. The authorities began to remove graffiti.”

“I noticed accumulated layers of imagery on the walls, which reflected changing times, and began to work with this. I dug through the different layers, like an archaeologist. Sculpting faces from the walls, I noticed how much images influence us, although we might have no notion of this at the time. I worked with advertisements, covering them with white paint. Peeling this away, I created images to reflect the fugacity of consumerism, and the dangers of living a lifestyle of credit and extreme consumption. Working in a boom in Lisbon, people were looking at the shiny new buildings, without paying any attention to their long shadows.”

“Travelling shows how globalised we are. Digging into buildings around the world I perceive how similar people’s lives can be. In Shanghai, like Rio de Janeiro, infrastructure projects are forcing people out to the suburbs or into big housing condominiums. Such new construction programs are linked to development and speculation, not social improvements for people who live in these places. The processes occurring in China and Brazil reflect what happened in European countries in the 1970s as they lifted themselves out of poverty. History is repeating itself.”

Looking at Vhils work, I can only wonder what Providência will look like four months from now.

?